Although many people must have thought that vinyl music records are long gone, record sales have actually been rising again in the past decade. This is not just about sales of used records but also of new albums and new editions of albums from past years. Moreover, not only veteran artists return to publish a vinyl edition of their new albums but also contemporary younger artists choose to publish their albums also as vinyl records. Not to be mistaken by any illusion however about this comeback, vinyl records are not returning to be a dominant format — they are still occupying only a marginal share of the recorded music market. Nonetheless, the revival of vinyl records is conspicuous vis-à-vis the newer technologies that have taken hold in the market since the 1990s.

In fact, this revival is not really ‘news’. The sales of records nearly died out in 2006. Yet soon after they have started climbing again — 2016 was the 10th consecutive year of growth in the US and the 8th consecutive year in the UK, mostly at a double-digit rate of growth. The renewed rise of records is catching attention because it happens to be the only format whose sales are increasing while other formats (e.g., CDs and even downloads of digital albums) are in decline. In a development that has attracted attention to this phenomenon more recently, in early December of 2016 weekly sales of records (£2.4m) for the first time surpassed revenue from digital downloads (£2.1m) in the UK. In the same period of 2015 sales of records reached £1.2m compared with revenue from digital downloads that was as high as £4.4m (The Guardian, 6 December 2016). Digital downloads are not losing indeed so much to vinyl records but primarily to streaming services — downloading or streaming digital content are closer substitutes, both more distinct from vinyl.

During 2016 unit sales of vinyl albums in the UK have risen by 52% to a volume of 3.2 million LP records, a record by itself. It was not the strongest year of growth (previous two years have seen a rate of ~65%), but that rate was nonetheless respectable, and over a span of four years the sales volume quadrupled. CDs remain the dominant format for albums: over 47 million units were sold in 2016, but that was 12% lower than a year earlier. Notably, downloads of digital albums fell 30% to 18.1m in 2016. Vinyl records account for 4.7% of album sales, physical and digital; while that is a modest share, it has mounted from 2.6% in 2015 and 0.8% in 2013 vis-à-vis a decline in sales of CDs and digital albums. (Source: British Phonographic Industry association, BPI, with Official Charts Company)

-

A metric of ‘Album Equivalent Sales’ (AES) attempts to accumulate digital and physical album sales together with album-equivalent content accessed by streaming (subscription). Out of the total volume of AES, physical albums accounted in 2016 for 41%, and vinyl LPs alone accounted for just 2.6% (up from 0.7% in 2013).

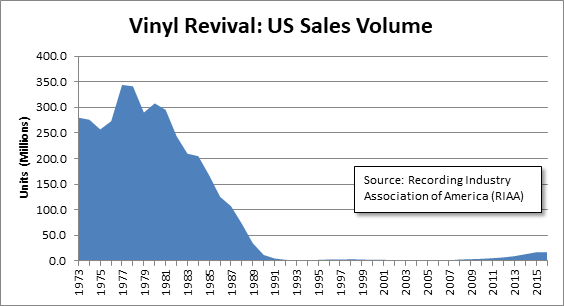

In the US the year 2016 overall was relatively poor in terms of growth rate (1.8%), nearly stagnant considering that since 2009 unit sales increased annually at rates between 20% and 40%. One might question thereof if the resurgence of vinyl LPs has reached its peak already or this is no more than a temporary halt. The better way to see this is to realise that after all the sales volume of vinyl album records has risen from a bottom level of about one million units in 2005-2006 to a level of 17 million units in 2015-2016, rising without a break throughout this period. (Source: Recording Industry Association of America, RIAA).

Even today CDs in the US (as in Britain) remain the more frequent album format purchased by consumers (99m in 2016), more than digital albums downloaded (86m). The sales volume of CDs was actually greater than digital albums all the time since the latter entered the market in 2004. However, CDs are no longer the strong force they used to be, far from it — in the late 1990s-early 2000s they reached levels around 900m, slide down to about 250m by 2010, and came below 100m last year. Yet, sales of digital albums (by downloading) that followed CDs got only as high as 116-118m (2012-2014) and are already coming down as well. Vinyl records constitute 15% of physical albums (up from 2% in 2011). Against this background the resurgence of vinyl record albums is at the very least intriguing.

The following chart shows the shifts between three main physical formats of albums followed by the digital format, based on the statistics of RIAA.

Vinyl LPs return as a small niche; since it constitutes less than 5% of the ‘album market’ it is difficult to discern the revival of vinyl records in the chart above (on the right-end). The next chart shows more clearly the new build-up of sales of vinyl after a long ‘silent’ period.

-

To maintain a common basis for comparison, ‘single’ editions in vinyl, CDs, cassettes and digital downloads are not listed here. Other formats covered by the RIAA include music video, DVD audio, download music video, and ringtones; notwithstanding, streaming (represented in ‘paid subscription’) is also omitted here (see detailed chart of RIAA).

Somehow it seems that digital albums never managed to replace the physical formats as in their primes. First, when it comes to downloads, it could be misleading to focus on albums because the major activity is in ‘single’ tracks. Unlike in the physical formats, downloads of ‘singles’ contributed from start much greater a volume than albums. Second, music listeners relatively quickly moved to on-demand streaming services, paid or free (e.g., Apple, Spotify — we can add to this video music clips viewed on YouTube). At the peak of digital albums four years ago (2013), 32.6m albums were downloaded in the UK — now listeners prefer to rely on streaming services (BBC, 3 Jan. 2017). The free services generate their revenue from advertising. Whether by downloading purchased tracks or by streaming, music listeners reveal stronger preference to create their own compilations or play-lists of songs (especially if one has grown up into the age of the Internet and mobile).

-

Notice the differences in the lists of artists leading the charts of 2016 in the UK in sales of vinyl albums (Top 10), most streamed artists, and combined sales and streams of albums (Top 10)(go to BBC).

The statistics of Nielsen Music for the US are somewhat different from RIAA though they indicate similar patterns. As reported by music magazine Billboard, 13.1m album units were sold in 2016 in vinyl format (making 11% of physical albums). Vinyl sales grew by as much as 10% over 2015 though at a lower rate than in previous years. It is also shown that CD album purchases are leading (104.8m) even compared with digital downloads (82.2m). However, the drop in sales of physical albums overall (-14%) is attributed to CDs alone (-16%). A press release by Nielsen Music suggests that listening to music through on-demand streams (audio & video) increases at the expense of digital sales.

Patrons of music stores in recent years could not ignore the re-appearance and spreading of larger displays of vinyl records — they became once again an integral part of the scene in store. This has emerged particularly as the domain of independent music stores following the demise or downscaling of large music and entertainment retail chains (e.g., Virgin Mega Store and Tower Records on the one hand and HMV on the other). While music fans started to return to independent stores, that was not enough for keeping-up their business. In 2008 American independent stores initiated the Record Store Day, celebrated on the third Saturday of April, to encourage music fans to visit and buy in their music stores; they accompanied this special day with new and renewed album special editions. Over the years the UK, Europe and more countries elsewhere have joined-in. The record store day has done miracles for reviving vinyl records: it helped to broaden the audiences interested in them and boosting their sales to new highs (Fortune, 16 April 2016). Records can now be found on sale in a larger variety of chain stores and are also purchased more frequently from online retail platforms. Vinyl records owe much to the independent retailers for their revival, but of course multiple parties benefit — producers, retailers, artists and consumers.

The segment first to be drawn by the comeback of vinyl records were music listeners in their 50s and 60s who have known records so well from their youth years. However, they are expanding from devout music fans of genres such as rock, pop, punk and electronic (‘New Wave’) into a wider audience of listeners (Baby Boomers and X-generation) with a feel for LP records.

Parents acquaint their children with this ‘old’ format and come with them to the store on record store days. People also return to buy record editions of albums they used to have but dumped them because they thought they were obsolete and will not be possible to play. Some buy them just for nostalgia or as collector items and may not actually listen to them. Yet BPI reports in its blog that over 300,000 new turntables were purchased in the UK in 2016, an increase of more than 60% — so more music listeners who return to vinyl do listen to the records again. Furthermore, Millennials show increased interest in vinyl records (Forbes, 12 January 2017), joining the original listeners to records.

On the latest record store day in Israel, an interesting mix of patrons was encountered at “The Third Ear”, one of the independent record stores in Tel-Aviv. As one might expect, there were mostly shoppers in their 40s+, but there was also a group of young guys who must have been in their early 20s at most. The latter were not browsing just CDs but gathered for a while at a display of records. Indeed, shoppers differed in genres and periods of albums they were browsing — whereas older shoppers were seen largely looking into albums of previous decades or newer albums of veteran performers, the youngest group focused on a collection of more contemporary music styles. Nevertheless, everyone seemed very busy, and more than a few appeared to know well what kinds of albums they were looking for. In an interview to business newspaper TheMarker, an owner of “The Third Ear” commented that in the past few years at least fifty new vinyl albums were issued in Israel — no one thinks that it is a great business, but things accumulate and it has built a mass not so bad (TheMarker, Hebrew, 26 October 2016). No vinyl records were pressed in Israel for twenty years, until about four years ago. A music store like this one can succeed by selling also CDs, music and film DVDs, and even turntables.

Vinyl records represent something different to music listeners from later formats of digital technology. From the early days of CDs there has been an argument about differences in the quality of sound between media formats and which has become even more intense with the transition to ‘file’ formats (e.g., MP3). In addition, the black records also feel differently as a physical medium — they signify tangible music, even better than CDs. Perceived similarities and dissimilarities are playing in shaping relations of substitution and preferences — analogue vs. digital and physical vs. virtual.

Proponents of vinyl records seek them for warmth and depth in the sound of music. It is widely accepted that the digital sound is cleaner than on records. But the sound on records is perceived more natural and authentic, even though a track may include blips and hisses once in a while. Note that misses can happen also on CDs, and if a digital file is damaged the whole track is often lost. Vinyl fans also prefer the records as souvenirs or artworks (including covers and booklets)(BBC). They may further carry an appeal of fidelity, romanticism and the ritualistic nature of the experience (Forbes). That is, records are carrying a sentiment missing from later formats. Another aspect not to be neglected is the ritual act that accompanies playing records — lifting the record carefully, wiping the dust, and putting it gently on the turntable before bringing the needle arm closer to the record and sitting to listen. Whether this a nuisance or a matter of bonding through touch with the music medium is a completely subjective matter. Yet, this bonding seems to have worked better with vinyl records than with metallic CDs. It is completely absent with virtual digital files.

Audio tape cassettes indeed are left forgotten. A great advantage of the cassettes was the ease of carrying them around and being able to hear music away from home on portable devices (e.g., Sony’s Walkman and compatibles) or in the car. They had, however, several technical flaws of working with a magnetic tape. It was a perfect fill-in that was just bound to fade away with the introduction of CDs and later portable media players (e.g., Apple’s iPod) for ease of handling and quality of sound.

As a digital medium, the CD could be more fluently substituted by virtual digital formats, files that can be downloaded from the Internet or listened to (and viewed) by streaming, as opposed to vinyl records. Nonetheless, streaming may actually contribute to purchases of physical albums in stores, particularly vinyl records. Music listeners search songs or other music pieces in streaming services, experiment with and experience them, get ideas, and after learning what they like look for the ‘original’ record album in a music store. Moreover, especially the younger listeners tend to continue their enquires online on their mobile smartphones while in the store. For senior fans, a shop owner in Brooklyn commented, it lacks some of the adventure and surprise of the old-fashioned shopping style for music (CNBC, 17 April 2017). Even so, adaptive changes in shopping styles can be tolerated if they happily lead to buying albums in music stores or shops. In the bottom line, it is acknowledged that vinyl records are desired for their tangible feel but with a warm sound, imperfect as it may be — “it’s highly personal” (CNBC).

Vinyl record fans emerge as a niche of music listeners. It is legitimate to question whether the rate of growth of record sales over ten years is sufficient for developing into a substantial and solid market segment. On the other hand, the way record sales have mounted is extraordinary given the conditions of technological evolution and competition in the music market. Vinyl records offer genuinely different, missed qualities of tangible feel and pleasure of listening to those who appreciate them. More marketing effort will be required to fuel continued growth — building on qualities of vinyl that make it special and encouraging more music listeners to join the niche (e.g., events, new and renewed editions, advertising in streaming services, and prompting more word-of-mouth and conversations in social media). Expansion of the vinyl niche can additionally benefit other sections of the recorded music market.

Ron Ventura, Ph.D. (Marketing)

Highly informative and insightful?

I find it interesting when you said that sounds recorded on a vinyl record have warmth and depth. When you said that, it convinced me to ask my dad whether he can get his jukebox repaired this weekend. That way, my sister can dance to our favorite albums next week at her wedding and revive our family tradition at the same time.

As a Generation Y native, for whom a turntable is a platform seen mostly in historical films and as a sentimental item in my grandparents’ house. I found the article very helpful, especially these recent years, when there is a revival of the platform, even if only a niche. Now I feel updated, ironically. Thank you!